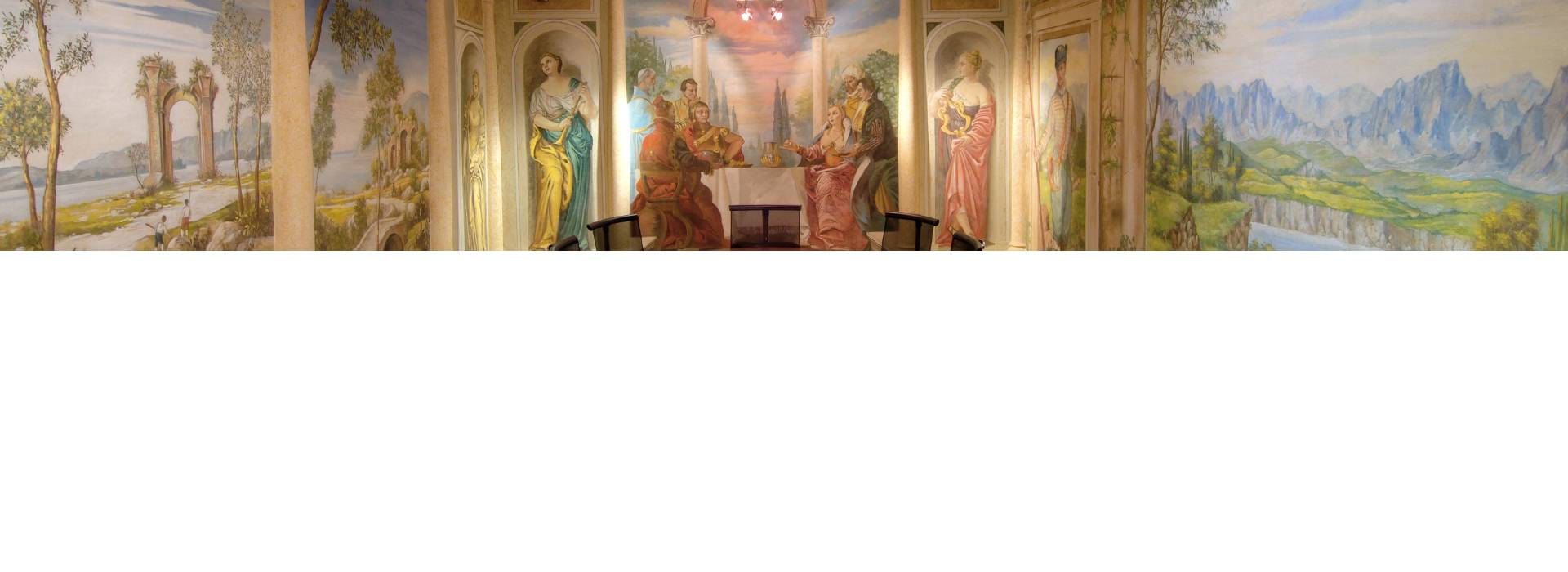

Fresco painting can be said to be the “mother of all painting techniques.” Invented by the Egyptians, it was then passed on to the Greeks, but Giotto was the one who turned it into the universally known technique that still fascinates us today.

The secrets of the fresco can be discovered in art laboratories, and surely start with the preparation of a good support or surface.

The first layer of rendering, known as the scratch coat, is applied to a brick wall using a trowel and float (or smoothing plank). The so-called sand coat is then applied with a long metal spatula and finally the finish coat to obtain a smooth and moist surface (from which comes the word “a fresco” – fresco meaning fresh) on which the painting is executed. This layer is made up of slaked lime mixed with clean river sand.

The preparatory drawings are drawn in full scale and are then transferred onto the wet plaster, which initially has a grey colour. There are countless ways to execute this step, from the use of charcoal or ochre to the most common, dusting.

The next step involves the study and choice of colours, evaluating which areas to paint first.

This technique leaves no room for second thoughts or uncertainties, and everything must already be prepared during the execution phases. In fact, the plaster absorbs the colour immediately, therefore, corrections cannot be made while executing the work, but only at a later time when the plaster has dried. The painting must be performed quickly and without errors, in roughly the same working day, keeping the support slightly moist with water.

Once dry, the grey lime present in the plaster turns white, incorporating the colours through the chemical process of carbonation which makes them stable and resistant over time.

This process takes place due to the presence of carbon dioxide in the air, which combines with the lime to form calcium carbonate. The grains of sand and pigments merge to become insoluble in water.

The colours used for fresco painting must be compatible with lime, or must be mineral colours because vegetable or animal pigments would be burned by the lime.

The pigments are diluted in water according to a process that requires special attention. In fact, pigments that are too liquid would not be resistant enough and would be “lost.” Instead, pigments that are too dense would not be completely absorbed by the lime and it would be hard to get a good colouring. The colours also tend to change hues once incorporated into the lime.

Theoretically speaking, fresco painting seems to be relatively simple however, as will become apparent after this introduction, it requires great skill in terms of execution. Just like in the Renaissance workshops, this technique can only be learned through intense practice, guided and coached by highly proficient Masters who have experienced the numerous surprises of this complex but fascinating painting technique.

By participating in a fresco course inside the Mariani Affreschi laboratory, students will be able to discover and explore one of the oldest artistic techniques in the world. They will see what actually goes into creating a fresco, experimenting with their own hands, from the execution of the initial sketch to the painting of a complete subject. They will learn how the colours react during the carbonation process, and which specific pigments to use in fresco painting. On completion of the course, students will be able to paint a fresco according to their artistic skills. It should be noted that years and years of practice are needed to master this technique therefore, each student can choose a training course according to their needs and their personal and professional goals, guided and assisted by a well-qualified teacher. Depending on the combination of these factors, the course will enable students to:

By participating in a fresco course inside the Mariani Affreschi laboratory, students will be able to discover and explore one of the oldest artistic techniques in the world. They will see what actually goes into creating a fresco, experimenting with their own hands, from the execution of the initial sketch to the painting of a complete subject. They will learn how the colours react during the carbonation process, and which specific pigments to use in fresco painting. On completion of the course, students will be able to paint a fresco according to their artistic skills. It should be noted that years and years of practice are needed to master this technique therefore, each student can choose a training course according to their needs and their personal and professional goals, guided and assisted by a well-qualified teacher. Depending on the combination of these factors, the course will enable students to: